Explore the first people in Sunriver

Look down at your feet. Are you wearing shoes? Maybe it's a pair of boots you wear to get around in six inches of snow. Perhaps it's a pair of heels you like because they've got style and are just the right height. Maybe it's a pair of slippers you only wear around the house when your errands are over and time to stay in for the night.

But, at some point today, you have used or will use a tool that over the millennia has helped humankind move forward by giving us the ability to walk quickly without worrying about what's beneath our feet. The first people to use this tool – which we lovingly refer to as shoes – lived in a series of caves at what is now Central Oregon's Fort Rock State Natural Area.

It's one of a handful of places you can visit while staying at a Cascara Vacation Rentals property and taking the time to learn more about the history of the first humans to call Sunriver home.

And, don't forget to pack a comfortable pair of shoes when you head out on your next great adventure. You might need them.

Fort Rock

When super-hot magma comes into contact with groundwater or the moist soil of a lake bed, it explodes into a jet of steam that carries bits of ash, rock, and lava hundreds of feet into the air. These particles cool when they fall back down to the surface and, in some cases, create a tuff ring-like Fort Rock – a 4,500-foot wide circular rock formation that's 53 miles south of Sunriver and climbs 200 feet into the air.

Geologists estimate Fort Rock formed 50,000 to 100,000 years ago. It sat at the bottom of a 150-foot-deep lake that held water from the melting glaciers and stretched 900 square miles across the Great Basin. This lake slowly emptied over the millennia. It's water flowing through rivers and streams into what is now the Pacific Ocean, seeping through the porous volcanic rock below or evaporating into the warming air above it. These forces caused the south end of Fort Rock to crumble, leaving behind an ancient fortification in the middle of nowhere that looks like it once protected a long-forgotten treasure.

An early pioneer, William Sullivan, recognized this shape when he stumbled across Fort Rock in 1873 while searching for some lost cattle and gave the rock formation its name. Sixty-five years later, Archeologist Luther Cressman shed light on the treasure these palisades protected: A prehistoric Paleo-Indian civilization and some sandals its members wore 10,000 years ago.

The first people

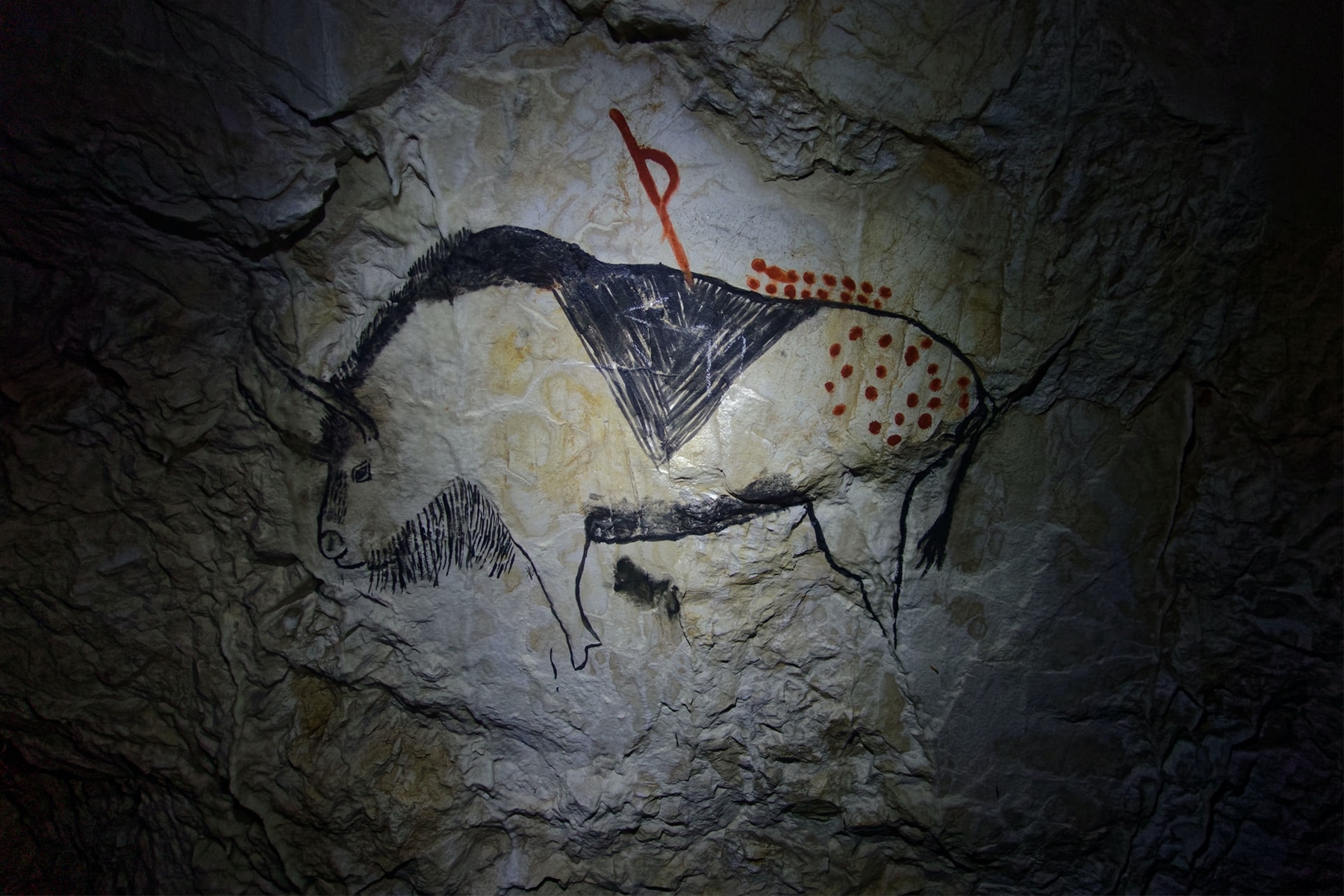

The Paleo-Indians were early humans who traveled in extended family groups of about 20 to 60 people. They followed mammoths, mastodons, and prehistoric bison over a land bridge that crossed the present-day Bering Strait from northeast Asia to the Americas.

The Paleo-Indians made sharpened projectile points and scrapers out of flakes of obsidian or flint they'd use to hunt wild game and harvest the animals' meat and skin. They'd also use these tools to collect edible fruit, nuts, and roots from the plants they encountered and slice the stalks from other plants into fibers they'd use to make baskets and other tools.

Cressman found hundreds of these tools when he discovered the Fort Rock Cave in 1938. It's believed the site was a small island surrounded by a prehistoric lake that the Paleo-Indians who lived there would cut across by canoes. They hunted the animals drawn to the site for access to the weather and ate the plants that flourished along its moist lake bed.

The shoes that Cressman found at this site, known as the Fort Rock Sandals, featured a flat sole and a protective toe cover made from shredded sagebrush bark and tightly wrapped twine. Archeologists estimate the fibers used to make these sandals date back to 9,000 years ago, making them the oldest pair of shoes in the world.

Subsequent waves of archeologists found Fort Rock Sandals at six other places across southeast Oregon and northwest Nevada. This list includes the Lava Island Rockshelter – about six miles south from Benham Falls on the Deschutes River Trail – where the Paleo-Indians butchered and processed the animals they had killed.

But perhaps the most significant archeological site in Central Oregon – Paisley Caves – is one Cressman excavated less than two years after his discovery at Fort Rock. Subsequent waves of archeologists found the projectile points, scrapers, and fossilized samples of human excrement Cressman discovered at the Paisley Caves site to be at least 14,000 years old, making it the oldest site of human habitation in North and South America.

The explosion

Every artifact archeologists like Cressman discovered at Fort Rock, the Lava Island Rockshelter, and Paisley Caves was buried under a layer of ash that blanketed Central Oregon when Mount Mazama erupted and formed Crater Lake.

The devastation wrought by this blast rendered most of the area uninhabitable and forced the Paleo-Indians who lived at Fort Rock and the surrounding area to scatter. Their descendants split into several Native American groups like the Molala, Klamath, Modoc, Northern Paiute, Tenino, and Tygh, which used Central Oregon as a year-round home or a winter refuge.

These groups followed a trade route along the Deschutes River and the Little Deschutes known as the Klamath Trail that connected the Klamath Lake Basin's marshlands with a major trading site on the Columbia River between The Dalles and Celilo Falls.

Hare, Central Oregon's first people met with other native groups from across the Pacific Northwest so they could trade obsidian rocks, captured slaves, and game for horses, dried salmon, and shells that they would transform into jewelry and other decorations.

Two hundred years ago, the Native Americans who traveled through Central Oregon along the Klamath Trail would meet up with white fur traders who hailed from Canada, France, and the newly-formed United States of America. Their journey through Central Oregon starts at a bend in the Deschutes River located less than a mile south of the world's last Blockbuster.